Metal Detector Hobbyist Discovers Valuable Treasure Worth Millions

Ever been out on a walk in the great outdoors and stumbled across an interesting find? If you’ve ever taken a glance at a history book, you’ll know that the world has been crisscrossed by empires and fallen civilizations since time immemorial. And where empires roam, wealth is sure to follow. While many of them were pillaged by the end, some left traces of their riches behind.

This is the story of an amateur metal detector enthusiast in England who stumbled upon an incredible treasure trove of forgotten gold, jewelry, and artifacts. He not only enriched himself with wealth, but he also shed light on a fascinating chapter of the human story. Read on to learn more about this would-be treasure hunter’s find.

Something Lost, Something Found

The story begins with the loss of a simple hammer. In 1992, late in the year, a farmer named Peter Whatling was making repairs on his property. At some point, he dropped something on the ground while digging a field. When he sat down for a rest, he found that he had misplaced his hammer.

Source: Pixabay

Peter was a mile and a half away from Hoxne, his home, a small village in Suffolk, in the southeast of England. Peter retraced his steps and searched the area for a great deal of time before realizing that it was gone. On his way home, Peter remembered that he knew someone who might be able to help.

A Good Neighbour

Peter’s friend and neighbor, Eric Lawes, agreed to help. He was a retired gardener and no stranger to losing tools himself. He was glad to help a friend in need. But Eric didn’t just have an extra pair of eyes to help—he had a special tool for the job.

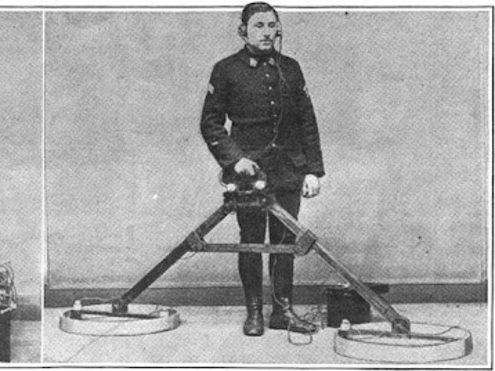

Source: PA Images via Getty Images

A few years before, Eric had received a metal detector as a retirement gift. He had taken to the hobby with some enthusiasm. While he had yet to find many artifacts of value before, he had helped plenty of his other neighbors find odds and ends when they went missing.

Finding A Signal

Peter and Eric took the countryside armed with the metal-object-finding device. Eric slipped on his headphones and began sweeping the field where Peter last saw his hammer. Strangely, Eric picked up an incredibly strong signal from below their feet.

Source: Robert Edwards/Wikimedia commons

The two were pleasantly surprised. The friends expected that they had miraculously stumbled upon the missing hammer on their first try. Eric propped the metal detector against a tree and got digging. But it wasn’t a hammer he found—it was a lost treasure trove.

The First Pieces Of A Fortune

Eric must have laughed at his good luck upon unearthing the first find. He dug up a spoon of solid silver. Then another. And then another. Just when he thought that was the end of it, he scanned the ground with the metal detector once again.

Source: Getty Images

The device told him that there was still yet more metal underfoot. Eric continued to spade up the earth and came up with more. Farmer Peter knelt in to examine the find: gold coins. But not just any old gold coins—they looked practically ancient.

Bags Full Of Treasure

Eric and Peter kept digging, but a hammer did not appear. Instead, they uncovered more gold, more silver, and even a few pieces of jewelry—all ancient. The two men were puzzled and giddy in equal measure.

Source: Peteruetz/Wikimedia commons

By the time they had finished digging for the day, they had enough treasure to fill up two whole grocery bags. The two men were exhausted from all their laboring, but still, the metal detector indicated that there was more beneath them. What they had was but a small portion of the true amount.

In For A Penny

A treasure hunter’s first instinct might be to keep the find secret, but Eric knew the special significance of what he had found. He also knew there was far too much for a simple gardener to excavate. Eric and Peter agreed that they had stumbled on a historic find.

Source: Impact Press Group/NurPhoto

After discussing the issue, Eric and Peter decided to get the experts involved. Some of their finds had spilled outside of Peter’s property. They contacted the local authorities, Suffolk County Council, and informed them of the treasure buried under the field.

Calling In The Specialists

Without digging up any more treasure or disturbing any more earth, Eric and Peter instead commissioned the help of the Suffolk Archeological Society. They reasoned that any further probing might potentially damage important historical artifacts.

Source: Getty Images

Soon, the Suffolk Archeological Unit arrived on the scene and prepared the area for an “emergency excavation.” Eric found himself amongst kindred spirits as he spoke to the archeologists who had brought their special metal detectors. The artifacts, as Eric has suspected, were of Roman origin.

Setting The Stage

An archeologist by the name of Jude Plouvier led the initiative. Rather than simply trying to extract more treasure right away, the team had to establish how extensive the hoard was. They searched a 98-foot radius before getting down into the dirt.

Source: Wikimedia commons

The team got to work meticulously brushing and removing the earth around the treasure. The team was no mere group of amateurs—they managed to extract the entirety of the treasure before sundown. So what did they find out about this mysterious hoard?

Finding The Source

The two grocery bags worth of treasure that Eric and Peter had uncovered on Peter’s property was only a fraction of the total loot. They had been tapping the vein on the edge of a larger mass of riches. The bounty was coming from one particular place.

Source: Getty Images

The archeologists discovered the primary source of the treasure—a great oak chest filled to the brim with precious metal. Other boxes were discovered around this chest—each one wrapped in fine cloth and fabric. Had they been hidden here on purpose?

Totaling Up The Find

Within the main chest and in the smaller chests scattered around, they found more cutlery—spoons of silver, precious dining wear, and intricate trinkets. They found no small amount of coins, jewelry, or golden statues.

Source: Wikipedia Commons

At the end of the excavation, the archeologists weighed their findings. They had, in total, 60 pounds of gold and silver—of that gold, 15,234 Roman coins in total. The whole heap was worth about $4.3 in today’s money

A Historic Find

This wasn’t just big news—it was the biggest Roman treasure hoard found in British history. Around 40 others had been discovered in the past, but in many instances, the findings had been immediately stolen or hidden. The pile Peter and Eric had stumbled on took the cake.

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Because Eric and Peter had called the archeologists right away, they were able to identify and catalog everything cleanly. This finding was important and shed light on several historical events.

Finder’s Reward

Eric and Peter were probably satisfied knowing that they had unearthed an important archeological discovery. But for their efforts, they were given a reward. But not just a portion—they were given a cash sum equal to the whole hoard!

Source: Getty Images

The valuables were carefully evaluated by the Treasure Valuation Committee over the course of a month. In the early part of 1993, Eric and Peter split a cool $2.43 million (£1.75 pounds) between them (an amount that would come to about $4.3 today, when accounting for inflation).

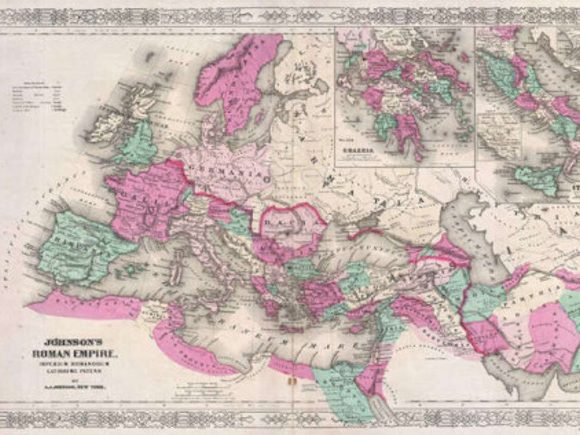

The Treasure’s Origin—Roman Britain

In 200 AD, Britain had been occupied by Roman forces for over 150 years. Cities were filled with bathhouses, aqueducts, amphitheaters, and many other kinds of architecture a citizen of Rome might expect to see in the capital itself. Although less impressive than other provinces of the empire, Roman Britain thrived.

Source: Carole Raddato/Wikimedia commons

In Londinium, Buildings with tiled roofs were a common sight. Goods in pottery came from places as far as Africa. But this prosperity—and all the riches it had brought to the island—was not meant to last.

Riches And Blood Spilt

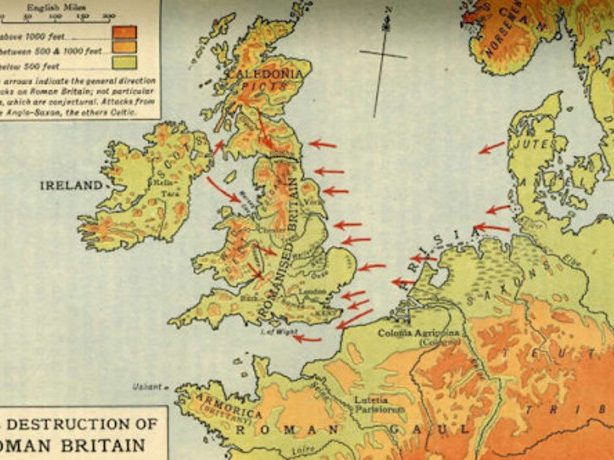

Roman Britain came apart at the seams, and by 450 AD, anyone living on the island might well have believed that the world was coming to an end. Emperor Theodosius outlawed any religion but Christianity, which created deep conflict among the polytheistic populous.

Source: Wikimedia commons

Worse, the east coast and its lands had been ravaged by Anglo-Saxon-Pict invaders. The province had been abandoned by the empire. Its cities were abandoned or destroyed, its people became illiterate once again, and its people began dwelling not in stone buildings but in primitive huts.

Hiding Riches From Invading Forces

Having been abandoned by the emperor and the empire, Roman citizens across the British isles were left to defend themselves however they could. Rather than letting the invading civilizations have their riches, many families opted to bury or hide what they had.

Source: Wikimedia commons

Fineries such as silver spoons and gold coins and trinkets were delivered to the earth after being wrapped. Who knows if these desperate citizens ever hoped to reclaim their treasures or if they simply wished to keep them out of the hands of their eventual killers?

Hoards And Hordes

Raiders also came down from Scotland and across from Ireland. According to some historians, citizens in what is now England hid their valuables as insurance against future attacks. They optimistically believed that they would be able to reclaim it should the worst happen.

Source: Unsplash

Would-be treasure hunters may be interested to know that while they did not invent the practice, Romano-Britains were the most prolific treasure buriers. If there’s a place to find treasure, it seems that Britain is not a bad place to start!

The Original Owners

Though it would be impossible to return the hoard to its original owner—given that the original owners would have died over 800 years prior—historians are still pondering the origins of this great fortune. Fortunately, thanks to Eric and Peter’s find, a few clues were made available.

Source: Unsplash

One of the golden bracelets is inscribed with Latin letters, which reads, “UTERE FELIX DOMINA IULIANE,” or “Happily use this, Lady Juliane.” Could this have been one of the original owners? Another name that appeared inscribed in several pieces was “Aurelius Ursicinus.”

Empress Pepper

Juliane and Aurelius may have been the couple living in Roman Britain who owned this great fortune—or perhaps these people could have been ancestors of the people who did. This statue could have been a depiction of Lady Juliane.

Source: Mike Peel/Wikimedia commons

However, it was found not to be a statue but a pepper pot. The archeologists who discovered this quirk creatively named the artifact “Empress Pepper Pot.” While there are many theories, there are no definitive answers.

Coin Clipping

One thing is certain about the hoard—the Empire of Rome had fully pulled out of the British Isles by the time it was put deep into the ground. They found this out by looking at the size of the coins. They found them to have been “clipped,” meaning they were much smaller than earlier Roman coins.

Source: Getty Images Images

The Romans hadn’t simply distributed new, smaller coins. The gold pieces had literally been clipped from the edges in order to smelt more currency. This description matched up with what the archeologists knew about currency-making at the time.

Precisely Dating The Hoxne Hoard

While historians have been able to narrow down the coin’s age by a few centuries, they ventured to narrow the dates down further. But this proved to be an unexpected challenge—in part because of the high quality of the valuables.

Source: Getty Images

Because the metal had been so pure, the archeologists and historians were unable to determine the coins’ ages with radiocarbon dating because they contained such small amounts of organic material. However, they estimated that the coins were minted between Valentinian I and Honorius’ reigns—around 408 or 409 AD.

The Story Gets Out

Naturally, the story about a great treasure discovery caught the attention of the national media. It sparked a revitalized interest in treasure hunting via metal detectors, in part due to a publicity stunt by The Sun, which promised its readers a free metal detector for answering a historical quiz question.

Source: Getty Images

“Who built Hadrian’s Wall?” Naturally, they received a huge influx of answers. Unfortunately, there was only one detector on offer. However, enthusiasts traveled to Suffolk to try and “sweep for gold” themselves. What began as an innocent discovery soon turned into a national frenzy.

Illegal Treasure Hunting

Not long after the word got out, metal detecting enthusiasts from all walks of life and of all experiences materialized in the area—especially nearby the original Hoxne Hoard site, where Eric and Peter had found their first spoon.

Source: Unsplash

This was all in spite of the fact that the local council had made metal detecting around the area an illegal activity. This was done at the behest of the archeologists, who did not want any further finds disturbed or destroyed by gold-hungry diggers.

A Second Excavation

One year after the initial find, the Suffolk Archeological Services discovered that many people had been digging their own pits in the hopes of finding valuables. In response, they set up another site, intending to oversee a second, more thorough dig.

Source: Wikimedia commons

Important historical information was at risk of being lost forever. The team began at the original site but took their search further, covering a much wider area than they had the first time—around 11,000 square feet.

The Results Of The Second Dig

It turned out that there was much more waiting for them in the area. The archeologists carefully brushed up 335 historical artifacts, each one a relic of the Roman empire. Amongst them, they found box fittings and more coins.

Source: Unsplash

According to the archeologists, the coins hadn’t been dropped by clumsy citizens. They were likely of the same original hoard. They had been spread across the fields by farmers during their recent east-to-west plowing of the land. Plowing from north-to-south, as it had been done before 1990, had not moved them from their original locations.

Golden Jewels

Historians counted 29 pieces of gold jewelry in the hoard. Citizens of the Roman empire were less discerning when it came to gender and jewelry, so any of the pieces—earrings, brooches, necklaces, and bracelets—could have been worn by men or women.

Source: Getty Images

The vast majority of these artifacts were over 91% gold—22 carats. Some pieces included elements of silver or copper in their design. Unfortunately for the historians, few names were inscribed on the pieces.

A New Law

The Hoxne Hoard was declared an official “treasure trove,” which is, by definition, a hoard that is buried and dug up in the future. Officially, the finder of a treasure trove has no right to a reward, but they are traditionally given a reward of some kind for doing so.

Soource: Getty Images

Since Eric and Peter were given the full price for the find, and since they split it, Parliament enacted the Treasure Act of 1996, which means that a founder, tenant, and landowner can split the reward—as previously it would only go to one individual.

The Mystery Of The Pepper Pot

Here’s another look at the so-called “Empress Pepper Pot,” discovered at the site and thought originally to be a bust or statue. It turned out to be a pepper shaker! Archeologists don’t limit her to peppercorns—it’s thought she could be loaded with other spices or herbs as well.

Source: Getty Images

Of the four shakers they found at the site, Empress Pepper is the most elaborate. Though historians maintain that she probably didn’t resemble any known figure in Roman society, they were puzzled by the scroll she holds in her hand.

Buried In The Backyard?

Using old maps of Roman Britain, historians determined that the hoard was not buried in a citizen’s basement or backyard. The riches were likely dragged a far distance from a family home, which was most likely a place called Scole—two miles northwest of Hoxne.

Source: Getty Images

Hoxne itself was not a great hub for Roman activity as it did not contain grand Roman architecture. Additionally, based on the layout of nearby estates, it is estimated that the Hoxne hoard was only a portion of the original holder’s fortune.

A Potential Candidate

A villa is referenced in a third-century record of roads and cities, Antonine Itinerary—drawn up under the administration of Caesar Augustus—called the Villa Faustini. Many of the spoons found at the Hoxne site had the words “Faustinus” engraved into them.

Source: Getty Images

The owner of such a mass of treasure would have easily been able to afford such a property. Unhelpfully, historians do not know where this villa was supposed to be located, and so the Villa Faustini hypothesis remains just that—speculation.

Organic Artifacts

Probably less headline-grabbing is the fact that other objects were unearthed at the Hoxne Hoard site. These included bones (animal), wood (mostly from chests), and, strangely, leather. Though the wood and leather can be explained, it is not known how animal bones got to be mixed in with the valuables.

Source: Getty Images

Historians know that the boxes were made of materials native to the island of Britain—yew and cherry tree wood. Linen and straw were used as padding to protect the silver and gold from the elements, but after 800 years or so, they had become quite deteriorated.

A Deeper Look At The Artifacts

Using X-ray fluorescence on various materials found at the site, such as glass, ceramics, and metals, the archeologists determined that many of the objects had been repaired over their lifespans. How did Roman Britons repair their broken things? Apparently, with mercury.

Source: Unsplash

Their objects were well looked after. Broken bowls were mended with mercury solder. Silver sulfide was also used to repair metals. In the home provinces of the Roman empire, lead sulfide was generally used to repair broken objects.

Using Rust Polish

Even to this day, jewelers use a variety of elements, including iron oxide—otherwise known as rust—to polish jewels. One of the artifacts found in the Hoxne Hoard contained traces of hematite, one of the other ingredients in rust rouge.

Source: Unsplash

If Roman jewelers were indeed using this formula to polish their valuables in Britain, the Hoxne Hoard would be the earliest known example of this “rust polish” technique being put into practice.

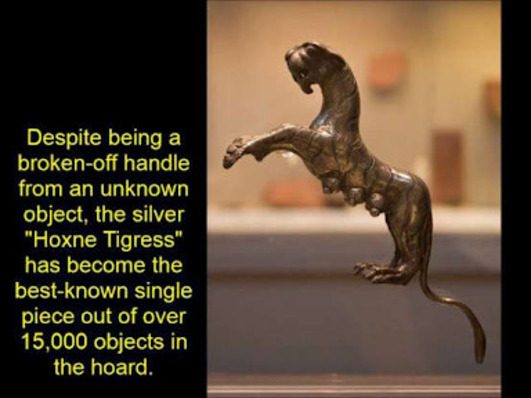

The Silver Tigress

This is perhaps the most interesting piece from the Hoard. Archeologists believe that several items went missing or were destroyed at some point in time. The appearance of this silver tigress indicates that there should have been a pitcher or vase. This would have been the handle.

Source: Reddit

Perhaps the vase it was once attached to was never buried, but its owners detached it in a desperate attempt to hide their riches. Or perhaps the pieces simply drifted elsewhere while modern-day farmers plowed the land.

The Hoxne Legacy

As well as renewing interest in treasure hunting and metal detecting in general, the Hoxne Hoard story helped show archeologists the potential of metal detectors in the field, improving trust between the researchers and the enthusiasts.

Source: Andrew Milligan/PA Images via Getty Images

The 1996 Treasure Act, which came about as a result of Eric Lawes’ and Peter Whatling’s discovery, also encouraged would-be treasure raiders to hand over future hoards that they might stumble upon—for the incentive of monetary awards and glory.

Further Adventures In Metal Detection

The discovery of the Hoxne Hoard, thanks to the media signal boost, also popularized the metal detector and the hobby of sweeping the ground for hidden trinkets. With a story like this, it’s easy to see the appeal.

Source: Wikipedia

But with all the lost civilizations out in history, there must be mountains of treasure out there, somewhere—waiting for a lucky detector to pick up a signal. And who knows—maybe a clue is lying there, out in the open, between the pages of a history book.